How can we know (or 'guess'?!) if our content is valuable to our audience?

Here's a 600-word article...then I share resources including a YouTube video, the original draft of the article with scaffold, and a screenshot of Clean Sequence 233466.

The only way we can know if our content is valuable to our audience is when they provide some data, for example by changing their behaviour in some way, by recommending our content to others, or just by continuing to read our stuff. Until there is contact with the audience, the best we can do is make informed guesses about the value of our content.

It follows that a practical challenge for ‘us writers’ is to make better guesses at an earlier stage. Because the better they are, the more likely that we spend time writing content that really does prove to be valuable and gets read and not wasted.

As we make those guesses about our content, I find it helpful to make a distinction between two aspects of content:

the ‘promise’ we make to our audience – this might be, for example, the title/blurb of a non-fiction book or a subheading of a section; and

the ‘paragraphs’ that make good on that promise. In other words, the main text or the body copy.

I elaborate on this distinction in this four-minute Youtube video.

Promise

Thinking of the ‘promise’, it should be possible to test its potential. At a very small scale, I have stood in bookshops with a few options for a titles/blurbs and I’ve asked random customers to rate the titles. At a slightly larger scale, I have posted titles/blurbs online and asked people to comment. At an even larger scale, there are online services where you can pay for hundreds of people to choose between titles/blurbs, giving a decent base size. By testing in this way, you can have some idea whether your ‘promise’ is resonating at all.

Paragraphs

Thinking of the ‘paragraphs’, it should be possible to measure value per page, where value is defined as providing content that moves the audience towards the promise made to them. A paragraph with relevant insights, takeaways, tools, actions or ‘a-ha’ moments will increase the value per page, whereas a paragraph that’s full of irrelevant fluff will reduce it.

Illustration

To illustrate this, allow me to share my guess of the potential value of the content in the article that you are reading now.

My ‘promise’, based on the subheading, is that I’m going to provide something related to content and value. I think that is likely to resonate with my target readers who generally want to write problem-solving (income-generating?) content rather than literary content. Say, 7 out of 10.

My ‘paragraphs’ have moved you towards that promise by:

a) stating that the way to know about the value of content is to look at data from the audience (which will be a surprise to writers who think they are the arbiters of value);

b) suggesting that content can be broken down into ‘promise’ and ‘paragraphs’ (which is likely to be a new insight for many readers); and

c) proposing that a writer can test the ‘promise’ and measure the ‘paragraphs’ (which could lead to new actions).

Given that the total article is 600 words, the value per page metric seems reasonable.

When I publish this short article I’ll see how many views, likes and shares it accumulates. If there are very few compared to the average of my articles, I’ll probably delete it and try again.

So, as you finish this article, please like it and share it if you think it’s valuable. But only if that’s really true! I’m trying to be guided by data so don’t just be nice to me. Good data is gold for me as I write things that help make a difference, with less fluff and more concentrated value.

<ends>

Four resources:

1. Rob Fitzpatrick writes about the ‘promise’ in his book ‘Write Useful Books’ which I thoroughly recommend to people who would like to design and refine recommendable nonfiction.

2. Watch me elaborate on the insight about ‘promise’ vs ‘paragraphs’.

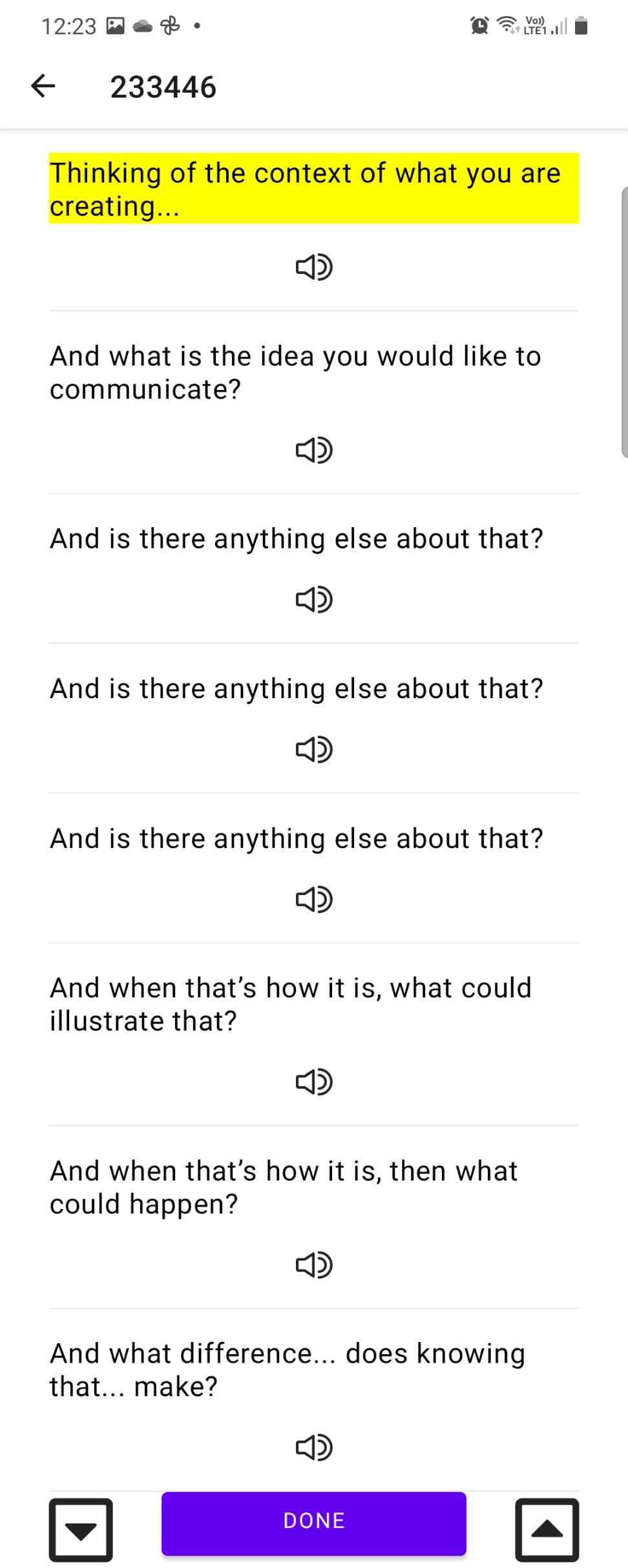

3. Here’s the original draft of the article that shows how the content emerged from a Clean Sequence (code = 233466). The questions posed by the Clean Sequence are in italics:

Thinking of the context of what you are creating...

My draft subheading is: ‘How do ‘we writers’ know if our content is valuable to our audience? Here’s one approach.’

And what is the idea you would like to communicate?

The only way we can know if our content is valuable to our audience is when they provide some data, for example by recommending our content to others, by changing in some way, or just by continuing to read our stuff. It follows that, until the audience has been exposed to our content, we can’t know about its value for sure. The best we can do is make an informed guess.

And is there anything else about that?

The practical challenge for ‘us writers’ is to make better guesses at an earlier stage in the process of creating content. The more accurate our guesses, the more likely that we spend time writing content that will get read and not wasted.

And is there anything else about that?

As part of this, it’s helpful to unpack the word ‘content’ into:

the ‘promise’ we make to our audience – this might be the title/blurb of a non-fiction book or a subheading; and

the main text that makes good on that promise.

In making this distinction, I’m again drawing on Rob Fitzpatrick’s ‘Write Useful Books’.

Thinking of the ‘promise’, it should be possible to test it. At a very small scale, I have stood in bookshops with options for a few titles/blurbs and I’ve asked random customers to rate the titles. At a slightly larger scale, I have posted titles/blurbs online and asked people to comment. At an even larger scale, there are online services where you can pay for hundreds of people to choose between titles/blurbs, giving a decent base size. By testing in this way, you can have some idea whether your ‘promise’ is resonating at all.

Thinking of the ‘main text’, it should be possible to measure its value per page, where value is defined as moving the audience towards the promise made to them. I’ve written Clean Sequence 476204 to help with this. A higher value per page can give confidence – though it still depends on the promise itself being valuable to audiences.

And when that’s how it is, what could illustrate that?

To illustrate this, allow me to share my thinking about how useful this short article might be to ‘us writers’.

My initial thought is ‘well of course it will be useful, that’s why I’m writing it!’. Hmm. That sounds self-indulgent.

OK, I’ll break it down. My ‘promise’ is in the subheading and the original version is ‘How do ‘we writers’ know if our content is valuable to our audience? Here’s one approach.’ So I guess the promise is that I’m going to provide something that helps my readers write useful/valuable content.

My main text moves readers towards that by a) emphasising the importance of data from the audience and b) suggesting two practical actions. Given that the total article is x words, the value per page metric seems reasonable.

What I can do now is to publish this short article on Substack and see how many views it gets. If there are very few compared to the average of my articles, I’ll probably delete the article and try again. I’ll also see how many shares it accumulates (useful data) and how many likes.

And when that’s how it is, then what could happen?

So, if you feel this article is valuable, please like it and share it. But only if you really do think it’s valuable! I’m trying to be guided by data so don’t think you have to be nice and encouraging to me.

And what difference... does knowing that... make?

Good data is gold for writers who want their content to be more than a means of self-expression but also a way to make a difference, with less fluff and more value for ‘us writers’.

4. Finally, here’s a screenshot of Clean Sequence 233446 on the Android app, which I used to draft the article:

If you’d like to try the app please get in touch with me via richard.dyter[at]facilitatedwriting.com